Currently reading

How the World Works

The English Auden: Poems, Essays and Dramatic Writings, 1927-1939

Auden Generation: Literature and Politics in England in the 1930's

Collected Poems

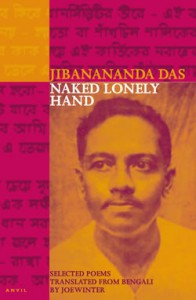

Naked Lonely Hand: Selected Poems

I have two volumes of poems by Jibanananda Das, translated by Joe Winter. Bengal the Beautiful is a collection of sonnets all concerned with the merits of Bengal, which I responded to very favourably; Naked Lonely Hand is more diverse in form and subject matter, selected from six collections and illustrating the range of Das’ work over his lifetime, so I feel justified in being more ambivalent. With both volumes, my initial response was often muted through cultural differences, major and minor, which become less problematic on second and subsequent readings, but never disappear. I would not claim to have any deep appreciation of them now; I can only give my personal response.

I have two volumes of poems by Jibanananda Das, translated by Joe Winter. Bengal the Beautiful is a collection of sonnets all concerned with the merits of Bengal, which I responded to very favourably; Naked Lonely Hand is more diverse in form and subject matter, selected from six collections and illustrating the range of Das’ work over his lifetime, so I feel justified in being more ambivalent. With both volumes, my initial response was often muted through cultural differences, major and minor, which become less problematic on second and subsequent readings, but never disappear. I would not claim to have any deep appreciation of them now; I can only give my personal response. The first nine poems are taken from Bengal the Beautiful, which I have reviewed separately. https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/2527079355?book_show_action=false&from_review_page=1

Seven poems follow from a collection called Grey Manuscripts. In “Before Death” – eight stanzas of seven lines each, without rhyming structure – Das invokes a rather mournful style, repeating the phrase “We who have ...” as an almost religious incantation to introduce diverse recollections of past times in an idealised rural setting, in a way that implies he is addressing others of his own advanced age (though it seems unlikely that the poet was of any great age when writing this): We who have walked the lonely stubble field... We who have loved the long dark night of winter ... We who have seen the green leaf turning yellow ... The lengthy poem “Sensation” appears to describe an inner turmoil and the sense that the poet is different from those around him, which might concern his vocation to be a poet; it has a lot of nice lines and thoughts but I struggle to integrate them into a clear theme. “Lonely Signature” may be a love poem, in so far as I can decipher its evasive lines, though I find it inauthentic. “Song of Leisure,” by contrast, seems to me a far more effective celebration of rural life, solidly constructed around clear descriptive language:

At the call of the field of crops we too are here

Giving up sunlight’s day, abandoning earthly fame,

putting a match to city - port – factory – slum –

down to this field we came;

....

The farmer has turned earth over and gone –

his new ploughshare, fallen to the ground, stays on –

on the old field an old thirst stays alert;

the owl shouts out the hour for us in flight!

“At Camp” is a slightly chilling account of a hunt, with a “decoy doe” whose cries draw the unfortunate deer from hiding towards the hunters’ guns. “Field’s Story” is constructed from four linked poems and has an extraordinary quality of story telling, and is also partly reminiscent to my ear of the style of a lyric from the Blues: “Meadow moon keeps his gaze upon my face...” Finally, “Vultures” establishes the exotic aspect of this poetry for one who will never see that part of the world.

In the next set of poems, from Banalta Sen, I have not made sense of the first, referring to Suchenata, which may be a woman’s name or may be a term meaning loving awareness, but it is no love poem and no poem to love. I did like the colloquial expression in the brief poem “The harvest was some time back,” creating a whimsical effect that works well. The poem “Darkness,” on the other hand, seems very mystical and psychologically deep and vague to the point of meaningless:

I have been afraid,

I have suffered pain, endless, relentless;

I have seen the sun as it wakes in the blood-red sky

ordering me to stand and face the world in the guise of a human soldier;

all my heart was filled with hate – pain – wrath –

as if the sun-beleaguered world had opened a festival with the scream of millions of pigs.

“Beggar” is a brief and sad poem, glancing kindly at a moment in the day of a street beggar. Until recently, a reader in England would have responded to this as an alien experience not unlike th earlier poem about vultures, but under the neoliberal onslaught the streets of England are now lined with beggars for whom the elements are sadly less tolerable. “Banalata Sen”, the title poem for that collection, is apparently hugely popular and much quoted in West Bengal and in Bangladesh; it is fairly brief and, while it has nice lines, it is very opaque and surreal; of this specific poem, the translator writes: “Unfortunately for outsiders the atmosphere is a culture specific one, requiring a special knowledge (of what is conjured up by the various proper nouns) of a sort not to be supplied by explanatory notes.”

The fifteen poems of the Great Earth collection are diverse. “Sea Crane” is a long address to the graceful and impressive bird, so blithely unaware of human history and sadness. “Lightless” is a somewhat eccentric conversation with a star. “Naked Lonely Hand” is the title poem for this selection, but I do not see why; it is far too surreal for my taste. “Corpse” is again surreal and hard to interpret, except to enjoy the descriptive language. “Ah Kite” is a pretty little nature poem. “After Twenty Years” captures a couple meeting again after a long separation, without hinting at the outcome to follow. “Grass”, “Windy Night” and “Wild Geese” are again pretty nature poems.

“Sankhalama” reverts to magical language, something Das and presumably his intended readers enjoyed, but his next poem, “Cat,” is playful in a way that crosses any cultural boundary, I am sure:

All day on my way out I keep meeting a cat:

In tree shadow, in sun, on a rabble of brown leaves

.....

All day long it tracks the sun,

Now it’s to be seen,

Now – where’s it gone? ...

I was even more disconcerted by “The Hunt” than by the earlier “At Camp:” this time the fate of the deer is even more unfair.

Dawn;

After a night eluding the leopard’s grasp

...

He is down in the river’s cold sharp wave

...[to] astound doe after doe with his courage and comeliness...

Yes, it all ends badly for the deer and upsets me greatly, but I suspect the poet may be on the side of the hunter. Then again, I have no idea what the next poem is saying; in “One Day Eight Years Ago,” we get no clear explanation for the blunt opening:

They say he’s been taken away

to the corpse cutting room...

“Said the Ashwattha Tree” and “The First Gods” are pleasingly magical and that seems to be their point.

In a selection of seven poems from the next collection, The Darkness of Seven Stars, is a short and very naturalistic poem, “The Foxes That,” which I loved. “Seven Liner” is strange but includes an unexpected reference to Lewis Caroll’s Cheshire Cat, far from home: “like a cat that’s no more there, with a foolish grin, an empty slyness.”

“Geese,” “Sky-Fade” and “Horses” lead on to an entertaining diatribe against critics: “On His Throne” which begins:

‘Better write a poem yourself –‘

I said smiling sadly; the foggy lump made no reply;

No poet he, this fraud, droning on high

On his throne of manuscripts commentaries footnotes ink and pens –

....

Well, I read poems and do not write them, which gives poets an audience and a market on condition they please me, unlike “Sailor” and “Night” which both passed me by. “Idle Moment” however, is an entertaining, anecdotal poem about three beggars and a beggar-woman chatting, to whom the poet grants a pleasing measure of true humanity.

...Tipping some hydrant-pipe water into their tea

they set about to be more steady and serious

with their lives, sitting on the damp pavement

and shaking their heads ...

The last five poems are taken from “Time Bad Time Black Time.” After “She” and “A Strange Darkness,” the poem “Daughter” concerns a deceased child of the poet, uncomfortably. “World Light” is a meditation, and perhaps needs a guide to explain its intention. Then the lengthy final poem, “1946-47”, is on a different level to any other in this selection: more ambitious and more difficult. I have read it several times but would not claim to understand it properly as yet, but it is fascinating and that is good enough for now. For a writer who chose Bengal as his subject in so many poems, it must have been a major challenge to address the period of India’s partition, and this poem is without question philosophically rich.

...

In this age there’s a deal less light all around.

We have wrung out the value of this long-lived world,

of its words work pain errors vows and stories

made of the fineness of thought, and so we have stored up

sentences words language and an inimitable style of speech.

Yet if people’s language does not take light from the world of feelings

it is mere verbs, adjectives, a haphazard homeless skeleton of words

that stays well way from the verge of awareness...