Currently reading

How the World Works

The English Auden: Poems, Essays and Dramatic Writings, 1927-1939

Auden Generation: Literature and Politics in England in the 1930's

Collected Poems

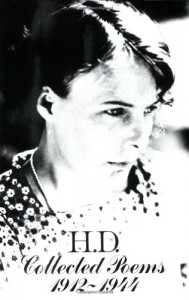

Collected Poems, 1912-1944

The poems from Sea Garden were accessible enough, but quite soon, in the selection from The God, my smart-phone was commissioned to check the Greek references. Euridyce in particular is only intelligible if the relevant myth is familiar, but once explained the poem stands out as clever and touching. By the time I reached Translations, in addition to searching out internet resources, I had excavated an elderly copy of the Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation (only recently it nearly left home for Oxfam) from the dustier part of my bookshelves, browsing both books in tandem.

The poems from Sea Garden were accessible enough, but quite soon, in the selection from The God, my smart-phone was commissioned to check the Greek references. Euridyce in particular is only intelligible if the relevant myth is familiar, but once explained the poem stands out as clever and touching. By the time I reached Translations, in addition to searching out internet resources, I had excavated an elderly copy of the Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation (only recently it nearly left home for Oxfam) from the dustier part of my bookshelves, browsing both books in tandem. I especially appreciated this blog, by “BriefPoems”, https://briefpoems.wordpress.com/2017/02/25/windfalls-fragments-of-sappho/

which discusses the challenge of translating the fragments of poetry left to us from Sappho, born some 2600 years ago in 650 BCE. The Catholic Church twice tried to burn all of her writings – in 380 CE and 1073CE. Books were handwritten and scarce in those days so it was actually feasible to remove all trace and we know a large amount is lost forever. Yet here she is today and when I found Sappho in my book of Greek Verse I was especially impressed by this little poem:

Forgotten

Dead shalt thou lie; and nought

Be told of thee or thought,

For thou hast plucked not of the Muses' tree:

And even in Hades' halls

Amidst thy fellow-thralls

No friendly shade thy shade shall company!

This is Hardy’s translation of Sappho and what the BriefPoems blog brings home is that another poet would produce quite a different interpretation of the identical Greek language original. As presented here, “Forgotten” is a poem by Hardy, inspired by a fragment from Sappho. What Sappho herself may have intended is absolutely conjectural and yet we have her writing to demonstrate that she was a poet and I am confident we can interpret this poem to affirm that one thing Sappho did hope for was to be remembered through and in her poetry, which in turn suggests that Hardy’s translation is a successful one; Sappho’s own project is thus victorious over Time and its vicissitudes.

There is nothing more engaging than the epics and plays brought down to us from the ancient Greeks, and H.D. has replicated this style to great effect, but the Oxford Book makes clear that what we retain of Greek poetry is often fragmentary or in the form of mere epigrams. Restoring such material requires a creative effort to capture an insight or meaning and present this in a form that is honest and also beautiful.

This challenge seems to have fascinated H.D. She takes every creative and artistic liberty allowed to her in order to establish in an entirely new work something fundamental about the Greek original. In Nossis [pp155-157], for example, she has taken quite a brief and poignant fragment and rendered this as a sixteen line poem embedded in one of her own that covers three long pages. Perhaps my favourite poem so far by H.D. is Heliodora, in which another fragment is translated but then placed as one element within her own truly beautiful invention, which is available here: https://allpoetry.com/Heliodora

What comes from all this is the suggestion that H.D.’s poems are not instantly accessible but they are not that difficult to tackle in this age of smartphones and search engines. With a modest investment, the rewards are plentiful, since her poetry is beautiful in its writing and in its sentiments. But if, with H.D.’s example in mind, you come across a copy of the Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation, snap it up at once; it is surprisingly wonderful in itself, and at the same time may provoke you to consider how the translations you find there might have been different.